I Am Graphics And So Can You :: Part 3 :: The First 1,000

Part 2 :: I Am Graphics And So Can You :: Intuition

Part 4 :: I Am Graphics And So Can You :: Resources Rush The Stage

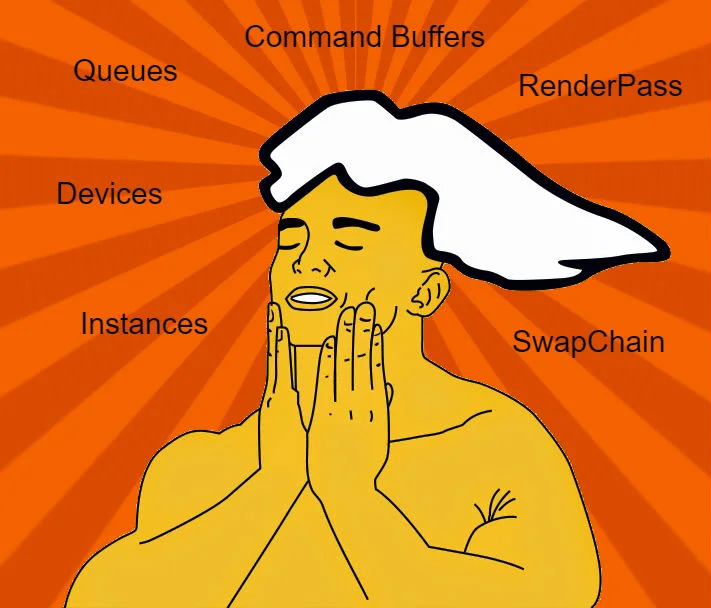

One thing people frequently marvel at is the amount of code Vulkan requires you to write. I often hear ( and have said ) "It takes 1,000 lines of code just to set things up." This is absolutely correct. But!!! Don't dismay. The impression is that, "man, if it's this difficult to set things up, how difficult is it to do any rendering?" But this isn't the right impression to have. Again, I'll let some data convince you.

In Part 1, I shared a sample video of what VkNeo can do. Since, I've also fixed shadow volumes, subviews, and other various things. All that's left are some postprocessing bugs, window resize bugs, and more play time. At this point in time the total lines of code that are Vulkan specific equals 4,816 across ~12 files.

VkNeo : Vulkan Lines of Code

So 1,000 lines really puts a dent in that final number right? That owes to Vulkan's philosophy in rendering and that is to eat as much of the cost up front as you can, so nothing is in your way when it comes time to draw. This is perhaps the biggest difference between Vulkan and OpenGL. Vulkan works hard before the party so it can let loose later. OpenGL is running around worried that everyone is having a good time.

What about shader code? Well thankfully you can write Vulkan shaders in GLSL ( with some differences ), so the amount of code is comparable. There are roughly 40 shaders in DOOM 3 BFG with VK GLSL totaling 3,875 and GL GLSL totaling over 4,500. ( A lot of that has to deal with how Neo generates shader code from idTech 4.5's own render prog syntax. )

If I implemented all the debug features native to idTech4.5 I'd have 9-10x lines of code. And this make Vegeta very happy.

So let's get ready to party and look at some code.

NOTE: Take time to read the code comments as they are part of the article. If you don't, you'll miss out on insights and overall intent. You don't want to miss out do you?

Let's take each of these items from top to bottom. Note that VK_Init simply builds a window, and Sys_InitInput does exactly what you'd think. So we'll bypass those for now and head straight to our first task. We need something to render to.

Creating A Surface

Vulkan does not expose global state. Instead it follows the idiom of using handles for referencing state. The very first thing you'll create is a Vulkan instance represented by the type ( VkInstance ). This is the front door to the Vulkan world, and is mainly used for getting information about the hardware environment as well as constructing other handles needed for rendering.

The validation layers are extremely helpful, so I suggest using them often. Now we have our instance and can move onto creating our surface.

Now we have our presentation surface. Next we should probably figure out a few things about the hardware environment we're running on.

Hardware Discovery

You don't always get the luxury of running on fixed hardware, so every good application should take a look at its "situation". In VkNeo this takes the form of EnumeratePhysicalDevices and finally SelectPhysicalDevice. The reason for the second one, is that the system might have multiple devices supporting Vulkan. I wasn't really caring to support SLI/Crossfire for an old game, so I just pick one to use.

Those new to graphics are usually overwhelmed by the volume of choices for options. For example VkFormat has over 180! But take heart, normally you'll only use a small subset of these and I'll try to point out which ones matter. For instance, of those 180, VkNeo only uses about ~12.

The other notable thing is presentation mode. This could easily be a blog post unto itself. For beginners it's safe enough to say, just take the best one available. And that will come up in the next function. If you want to dig deeper go to vulkan-spec and search for vkGetPhysicalDeviceSurfacePresentModesKHR.

I keep promising to bring up queues. They are the unsurprisingly what you submit work to. When you eventually start sending commands to the GPU, they will be given to a queue. Queues are a way for the hardware vendor to represent capabilities to you the software developer. There are graphics queues, transfer queues, compute queues, etc. Really for beginners you only need to worry about graphics and if it supports present. Hey, I know! Let's go create some queues now.

Work Work Work

Now we get to two of the most often referenced things in the Vulkan API; the logical device ( VkDevice ) and the queue ( VkQueue ). I just talked about the queue, but what is the device? "I thought we already went through the physical devices" you might say. The logical device is simply an interface to the physical device. It exposes the underlying API of interacting with the device. Let's take a look.

As you can see this was fairly straight forward. The next few items aren't necessarily order dependent, but it's just how I chose to implement things.

In Vulkan it's your responsibility to properly synchronize access to resources. ( This can sound scary if you're a beginner, but don't worry. I'll dispel the fog for you ) The primary thing you synchronize access to are the images you're rendering to and the images you are presenting. There are many means of synchronization in Vulkan, but for this task we'll use semaphores ( VkSemaphore ).

Well that was simple! Notice I'm creating semaphores for NUM_FRAME_DATA. This is because in VkNeo I double buffer my frame data. Those familiar with double buffering get it. But if you're a beginner all it means is while you're showing one image, you're building the next one. Then when you're done working on one image you display it and use the previous one to begin the next frame.

You know what. Enough talk. Time for a video intermission.

Now let's move on with command buffers. Command buffers are your way of instructing the GPU. A lot of the "active" Vulkan API takes a command buffer as an argument. Think of it like a server taking your order at a restaurant. They write down your intent and expected outcome, and then take that back to the kitchen ( the GPU ). The kitchen then translates your order into specific instructions it needs to perform in order to produce the outcome you expect when your food is finally delivered.

Notice the addition of a new synchronization primitive? This time it's a fence. I use these to wait until a previous command buffer is done.

I'm going to skip over this next part. The idVulkanAllocator and idVulkanStagingManager relate to memory management and getting things to and from the GPU. For that reason they deserve their own article.

// Setup the allocator vulkanAllocator.Init(); // Start the Staging Manager stagingManager.Init(); /* See you soon guys! ____ ___ . ,, ,, . ', \,__ __,'',/ . .:>}}Y{{<:. .' \ \/' ./ ' .'. ''W' ' .' . \ / " \ / ,-----------"--, | \____/' /-\ \ Row faster! \ ' .O `\ / | ,-- |\_______) O O | <' , "/ / / / ' .'; __ /N___/N____ `, '~~~' /'/'/'/' .',.'.`/' /' ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~D~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ */

Actual Rendering Resources

Ok so now we're getting into actual rendering resources. First we'll start by introducing the SwapChain. Basically this is just a collection of images provided to you from the device. Like in my double buffering video, the two sheets of paper I was playing tic-tac-toe on represent the swap chain images. Let's acquire them now.

The code comments do a fairly good job describing what's going on. By now though you can start to get a feel for how you work with Vulkan. The idioms I find fairly pleasant. The difficulty really is understanding all the options available to you. To that end I encourage you to take time to read about specific options if you find yourself perplexed. Vulkan's documentation is very thorough, and I can also heartily recommend Graham Seller's red book. ( See bottom of article for link )

Ok, so we have some color images, but what about a depth buffer? ( If you're brand spanking new to graphics let me know and I'll write an article covering that ) It's up to us to create a depth buffer, Vulkan don't care.

Now that we have actual images to render into let's move onto probably one of the more perplexing concepts in Vulkan. The VkRenderPass is definitely something that takes some getting used to. Essentially the renderpass is an orchestration of image data. It helps the GPU better understand when you'll be drawing, what you'll be drawing to, and what it should do between render passes. I promise after hearing that, and looking at the code, things will start to make sense.

See not so bad, right? While it is an oddity, it's something you can easily come back to. As I mentioned, I only have one, and look what I can accomplish with that!

There's one last thing we need to talk about, and that's Frame Buffers.

We made it! Time to party!

Obviously I did skip a few things, but that's because I want to save them so we can give them the focus they deserve. Instead of coping out on you, I'll explain specifically why.

- idVulkanAllocator - Memory management is easily an article in itself.

- idVulkanStagingManager - This gets into resource management for the game.

- idRenderProgManager - This deals with Vulkan pipelines and is arguably the most important part of using Vulkan

- idVertexCache - Again this deals with resource management and warrants its own discussion.

Well thanks for making it this far! I hope you find some of this helpful. I do intend to open source VkNeo soon so you'll be able to look at the full code for yourself. In the meantime if you have any comments, corrections, or solid trolls please share.

P.S. If you've made it this far, remember you've put a solid dent in getting things rendering. This easily accounts for 20% of VkNeo's Vulkan code. So hang in there, you've learned a lot today. Next we'll tackle memory and resource management.

Cheers